BackVisual Culture From Shashin to hip-siòng

BackVisual Culture From Shashin to hip-siòng

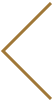

With the reproducibility of images used as a tool of colonial administration during the Japanese colonial period, the regulation for photographic equipment and material was tightly controlled by the colonial authorities. It was difficult for a native Taiwanese to operate a photo studio. During World War II, photographers had to register with the intelligence agency. This led the everyday use of photography to come under severe restrictions. With the Japanese government seeking to promote immigration, vocational schools that taught photography were set up in Japan and there was a large number of Japanese who set up photo studios in Southeast Asia.

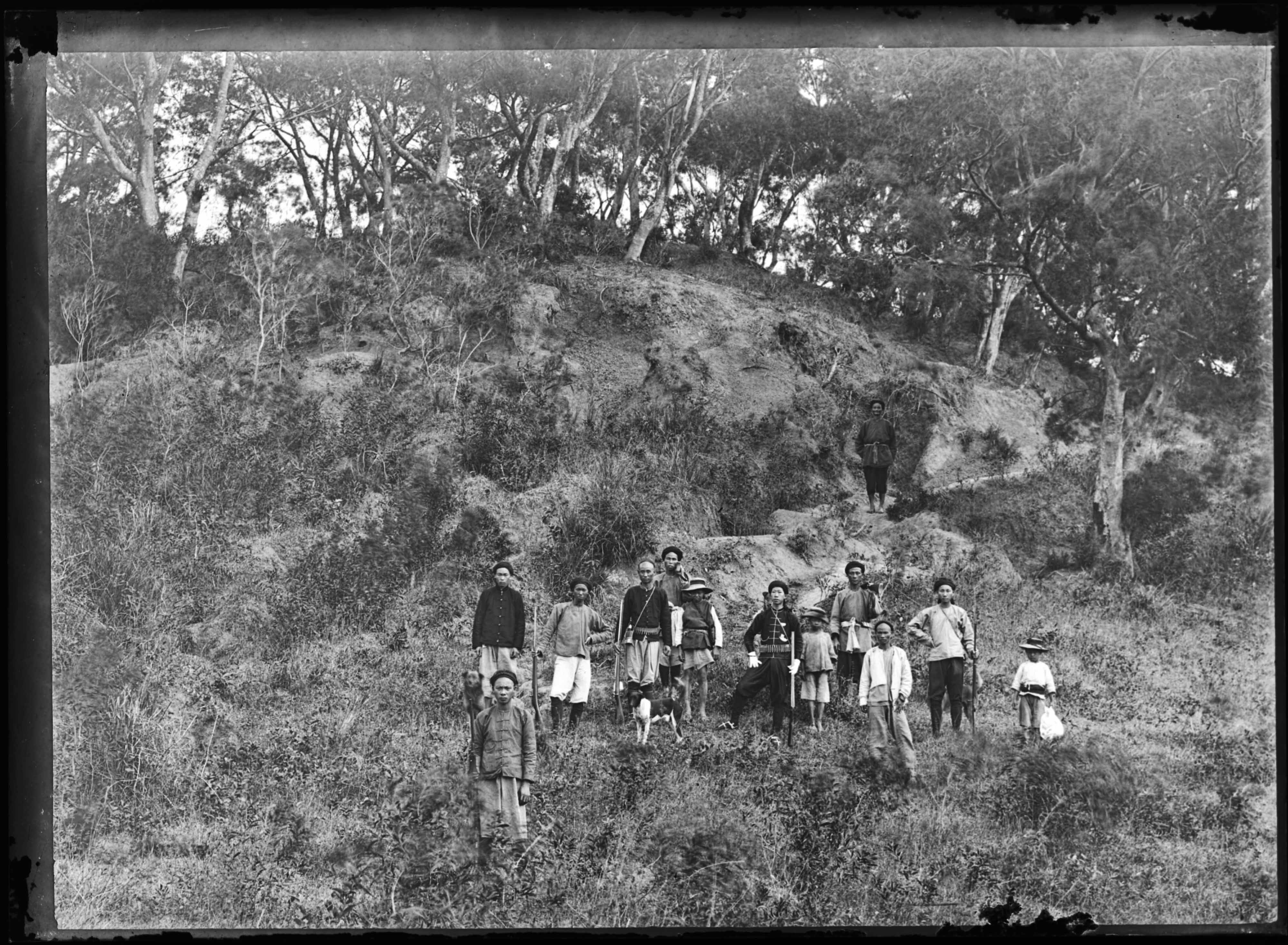

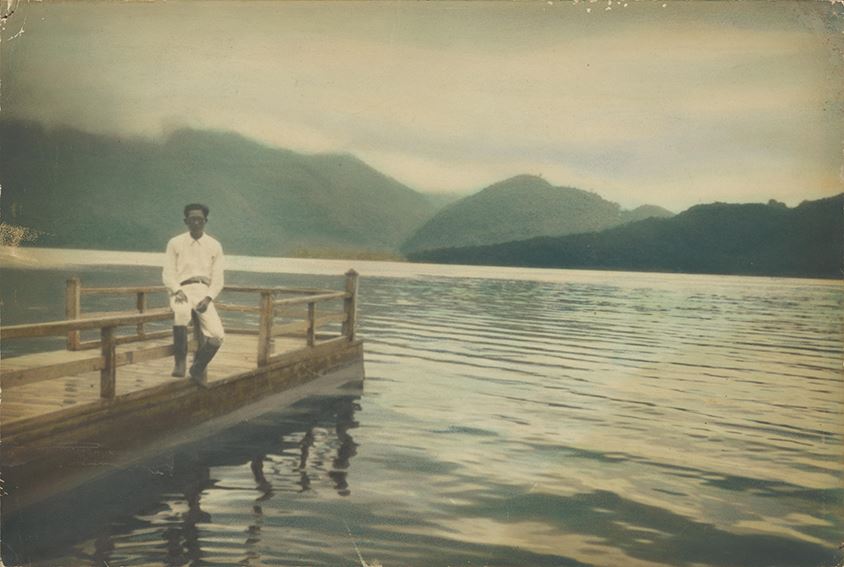

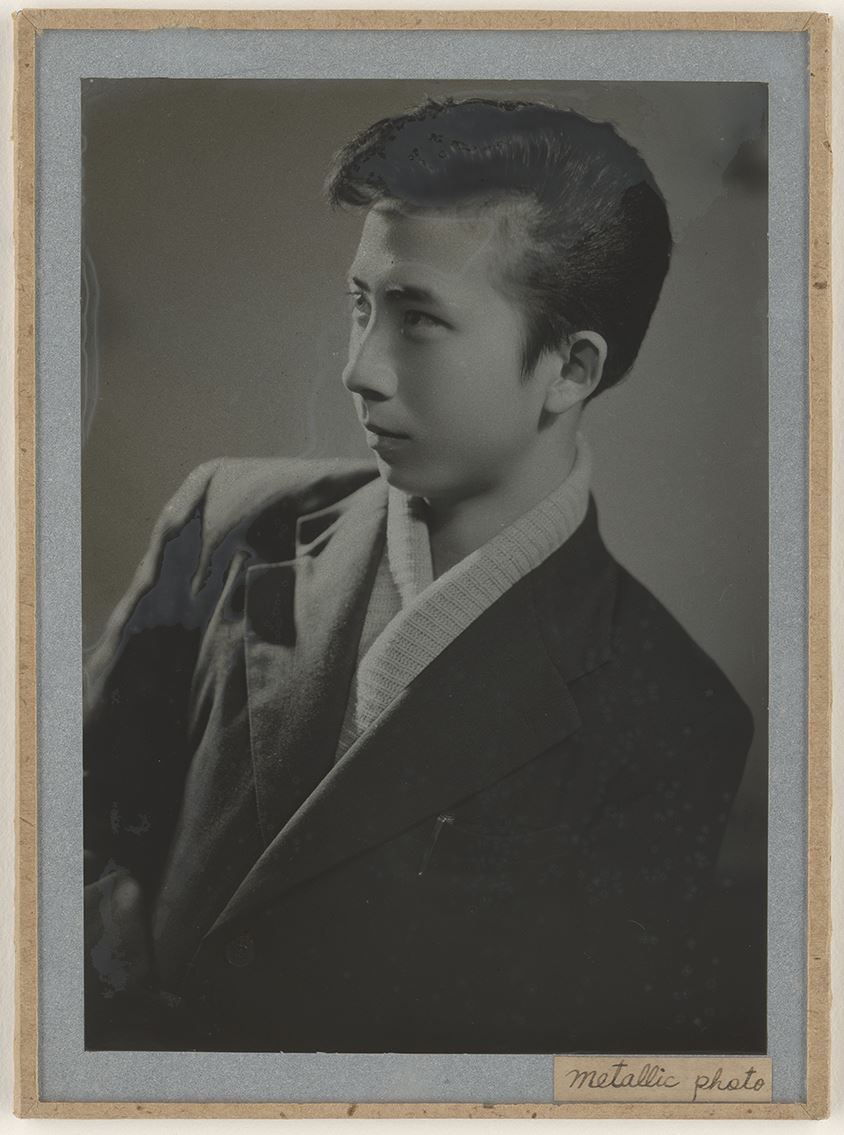

The use of techniques for reproducing sounds and images were heavily regulated by Japanese colonial authorities, but this still could not suppress the democratic potentialities of these technologies. Pierre Bourdieu’s ideas are elucidating regarding the notion of “middle-brow art,” regarding how this concept was constructed in the choice of what is photographed, as well as how photography itself can form a social relation, and become a cultural index in observing everyday life. Photo Studios not only document Taiwanese modernization, but also become a social practice of photography as a mid-brow art. In this period, photography became a public sphere with the formation of photography societies and organizations. “Shashin” in Japanese can mean “portrait”, this reflects the close relationship between portraits and photography in Japanese culture. In schools of portraiture, taking portraits and using lighting was a large part of the curriculum. By contrast, the term “hip-siòng” used in Taiwanese dialect was derived from “xi”, meaning to “intake” the image into the machine, just like how the camera does when taking pictures. When Taiwanese set up portrait studios, the standard business included portraits, wedding photos, exterior shots, and group photos. Techniques for using light in darkrooms played an important role in the development of visual culture in Taiwan.

Just as the double simulation of colonial images reached its apex, one saw the universalization of photographic equipment, allowing regular people to treat photography as a hobby. Under the refracted colonial gaze, Taiwan’s modernization was documented through photography. But one can also see how Taiwan’s sense of identity gradually transitioned toward its modern liberation through examining photographs from this period.

,男子合照.jpg)